I saw

this story in Bloomberg magazine a couple weeks ago, so I decided to speak with Ric Bratton again on the history of the low volatility effect. I wanted to speak more about other people's work, especially Ed Miller and Bob Haugen, but somehow we missed that (it's one take and he leads). In any case, here it is.

The risk premium is central to Asset Pricing Theory, one of the main things people learn in business school. If itâs not true, this generates a very different way to assess investments. Below is an outline of what I consider to be the history of low volatility with links to relevant articles. I should have a new paper out in a few days related to my 'solution' to the low volatility effect.

Economics has been hijacked by cargo cult thinking that superficial similarities with physics is the way to create good new theories (eg, see Samuelson's

Foundations). As rigor and logic are both more correlated with successful physics and easier to teach, these are the main emphasis at top graduate schools. Alas, rigor is always parochial, because outside a set of small assumptions the rigor doesn't work, which is why no proof in econ has changed anyone's mind about an important issue. Thus, in finance we had decades of focus on technical econometric issues (e.g., simultaneity of estimating the slope and the intercept, randomness in the risk-free rate, GMM tests of overidentifying restrictions), but not size (market cap) or low-price which would have killed the CAPM in utero. The omitted variables bias and overfitting remain the main scourge of social science empirical research, but that is only taught incidentally.

Back in my day you couldn't publish a paper showing high volatility had lower returns than low volatility because there was no theory for it, so it must be wrong in some technical way, and thus uninteresting. One reviewer told me that if I was to show low volatility had higher returns than high volatility I had to show how low volatility had more risk, which was what I was arguing wasn't true, That is, the main paradigm has to hold.

A led to strange threads within the low volatility history such as

Harvey and Siddique's 2000 paper on sknewness and returns. To the degree skewness relates to returns, it's incidental to the low volatility anomaly. Yet back then you could not address it directly because it was too anomalous to standard theory--utility functions imply some kind of risk premium in an

iff sense, they both imply the other. So, they document that 'co-skewness' (which is positively correlated to volatility), is an extra preference by investors. This allows them to nest their finding within the standard paradigm, because understandibly people like the right tail of a distribution, not the left.

Yet, while they set up the model with the utmost rigor, they never paused to see if their results were

consistent with global risk aversion. It's not. More practically, the counteracting effect in the Fama-French 3-factor world isn't skew, it's more basic, just volatility; no one makes 'low skewness' portfolios, though common low vol portfolios are correlated with that.

Harvey was for a time the editor of finance's best known journal, The Journal of Finance, and so represents the conventional wisdom of the best academics. Yet this paper is obtuse, they kind of result that gives the word 'academic' the implication 'clueless.'

Another great example is

Ang, Hodrick, Xing and Zhang's now seminal 2006 paper documenting the volatility effect for the first time in a top journal. Bob Hodrick is a very prestigious academic, and was on the faculty at Northwest when I was there in the early 1990s, and I showed him my results that low volatility portfolios generated huge 'alpha's in the context of Fama-French 3-factor models, and he couldn't have been more indifferent. Yet, 12 years later he basically scooped me within the academic literature (my dissertation findings never made a journal).

The trick was that he presented these findings as an addendum to a paper that primarily addressed the extension the returns are a function of changes in volatility. Now, at 30k feet this is a within-the-box extension of the standard model, but note they found it had the wrong sign, that is, stocks correlated with changes in volatility were volatile, and these had lower-than-average returns. Think how bizarre the scientific method is when you are incented to present a new finding as within the paradigm, and cleverly elide the 'wrong sign' issue by casually noting the 'price of risk' is negative. What does that mean in this context where this clearly isn't some kind of insurance? When Ang et al got to the part of the paper that was actually interesting, the low volatility effect, they then dropped any pretext of a model (as was laid out for their new volatility innovation factor) and showed the tabular results of alpha by volatility, which was the big addition to the literature. At the time (circa 2006) this was the kind of pretext still needed to introduce this result.

That's why the CAPM has dominated academic thinking for decades in spite of it never actually working.

After

Freakonomics (2005) and Kahneman's Nobel prize (2002) became famous partial equilibrium empirical findings were publishable in top papers without much motivation, so we see less silliness anymore (alas, the pendulum has perhaps gone too far the other way). Of course, if you are famous, you could have always gotten a break from an editor, which is why the seminal refutation of the CAPM came from Fama and French, as only they had the credibility to publish a paper seemingly refuting the paradigm (plus, they softened the blow by merely extending it). This phenomenon highlights a strange behavioral bias to the wisdom of smart crowds whatever their pedigree; arguments are strongly constrained by authority and consensus in fields where you canât do definitive experiments.

Every successful theory has both a principled and unprincipled support; most people who spout correct theories do so for incorrect or selfish reasons. For example, listen to a radio call-in show on some topic you agree with, and note most callers have dumb reasons to agree with you; most people are wrong even when they are right. The ârisk begets returnâ theory was very convenient for hucksters because they could argue that their vague ârisk managementâ skills generated excess returns, which is tenable because presumably risk is omnipresent and subtle, like the quality of a fine wine. The theory was also very convenient to economists because it is perfect for teaching a course, where a set of seemingly innocuous assumptions creates a clear set of implications and is amenable to many rigorous extensions. At bottom, the CAPM made logical sense, so it had a principled rationale as well.

Researcher have always thought has occurred that if we can only define our terms, find the basic unit for an indicator, we can create a new science. The idea that investing would become an exercise in mathematical optimization is very attractive.

As Kant argued, there are two types of knowledge, assumptions vs. theorems,

a priori vs.

a posteriori. Assumptions are contingent, empirical, we infer them from data, and inference is imperfect, whereas theorems are logical and can be proven. Laymen feel that facts are easy and theory is difficult, but this is misleading. Surely smart educated people are better at theory, and so like to spend more time there, but conventional social science facts have always contained major errors.

The most exciting phrase to hear in science - the one that heralds new discoveries - is not "Eureka!" but "That's funny...", which is how the low volatility anomaly was born. Unlike size or value, it isn't an anomaly so much as death blow to the standard paradigm. You canât rationalize volatility as a risk factor because its return has the wrong sign with everything intuitively risky (covariance, leverage, size, liquidity, distress). Further, you can't simply add frictions to conventional model to get this as an equilibrium result, unless you invoke massive irrationality, and this isn't tenable because most investors are not irrational in the same way, thereâs too much incentive (e.g., money) for that to work.

The arc of how a pillar of science, the CAPM, was created and fell (or, is falling)...

- Profits and thus stock returns were a mystery up to 1950

- Persistence shouldnât happen in competitive equilibrium

- See Marx, Marshall

- Knight (uncertainty, 1921)

- Schumpeter (innovation 1942)

- Risk begets return theory developed 1947-62 (CAPM)

- Risk premium on investments comes from an if and only if relation to standard economic assumptions, one implies the other and vice versa

- Followed creation of macroeconomics in the 1930âs, which basically tried to apply microeconomics to an aggregate (macro also unsuccessful)

- See von Neuman and Morgenstern (1947), Friedman and Schwartz (1948), Markowitz (1952), Tobin (1958), Sharpe (1962)

- Empirically confirmed via the 'equity premium' estimate of 9.0% by Lorie and Ficher (1964).

- CAPM assumed true 1962-1992

- Initial tests of the âCapital Asset Pricing Modelâ (CAPM) were not supportive of the idea âbetaâ measures of risk,

- Sharpe, Jensen, Treynor and Mazuy

- but still made cover of Institutional Investor Magazine in 1971

- Douglas (1969) found little support

- Miller-Scholes (1972) added a bunch of corrections, but not size

- Statistical tests âconfirmedâ CAPM in 1973

- Fama-MacBeth, or Black, Jensen and Scholes

- Nothing is so convincing as an anticipated discovery

- Same papers used as proof through 1990s

- CAPM shown incomplete 1992+

- Size explains âbetaâ, beta explains nothing within equities

- Fama and French 1992, important Fama wrote paper

- New 3-factor F-F model, where 'anomalies' are now 'risk factors'

- Funds based on size and value blossom

- Turned asset pricing theory into a framework, not a theory

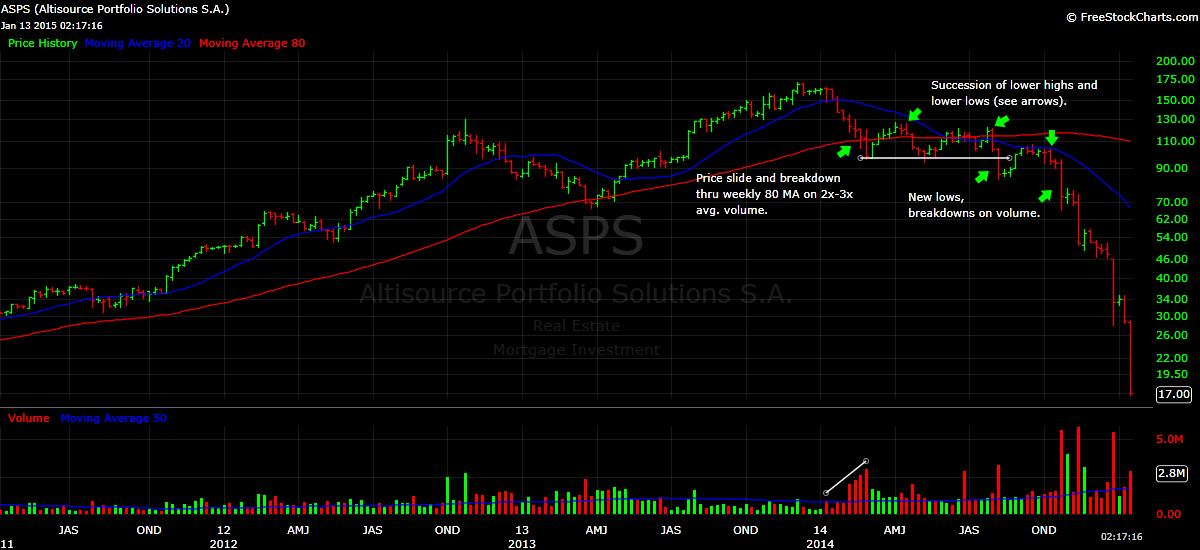

- Low vol anomaly 2006+

- Ang, Hodrick, Xing and Zhang (2006) first big pure academic paper

- Finding incidental to paper looking at factor based on a covariance with volatility innovations, and found a slight correlation.

- Bigger finding was that returns were lowest for the highest volatility quintile.

- Ang, Hodrick, Xing and Zhang (2009)

- Updated volatility to international

- Alpha falls off a cliff for high vol stocks

- Funds and papers start in 2006

- Clarke, de Silva, and Thorley (2006) at Analytic Investors

- Blitz and van Vliet (2007) at Robeco

- Asness, Frazzini, and Pederson (2010, 2013) at AQR

- Baker, Bradley and Wurgler (2011) at Acadian.

- Analytic Investors, Robeco, Acadian all created a low vol funds around 2006, subsequently outperformed benchmarks with 1/3 less volatility.

- Lots of data show this pattern generalizes

- For equities: Beta, distress, leverage, penny stocks, options, IPOs, analyst disagreement, mutual funds, over time within a country, across countries

- Private equity, C-corps, currencies, corporate bonds, yield curve, futures, movies, sports books, lotteries, real estate, hedge funds, CTAs, merger arb, senior vs. sub distressed debt, peak-peril vs. rebalanced reinsurance portfolios, low vs. high moneyness converts

- See my books Finding Alpha (2009), The Missing Risk Premium (2013)

- How did we miss this from 1960âs to 2006?

- Given standard assumptions, should be true

- Consistent with basic economic assumptions about utility functions increasing at a decreasing rate

- Intuitive and logical

- Creates mathematically beautiful models of endless application

- Keys to a convincing theory: simple enough to be apprehended without much strain but convoluted enough to require a caste of interpreters.

- Focused on statistical techniques

- Explanations today would not work prior to

- Behavioral Economics â Kahneman Nobel Prize (2002)

- Freakonomics (2005)

- Eventually the truth gets out

- With hindsight, lots of early papers saw this

- Richard McEnally (1974) found high risk stock to have lower returns, and suggested the following reasons that are now considered highly relevant:

- Seek access to high beta because of leverage constraints

- higher taxes on capital gains

- delusional investors

- skew preferences

- Bob Haugen

- Haugen and Heins 1975, Haugen and Baker MVP 1991, Haugen and Baker Common Factors (1996)

- In 2008, Haugen found out the low vol funds were all referencing his work, and then claimed to be the âfather of low volâ investing. He didnât emphasize this in real time, however, rather he emphasized a multifactor alternative.

- Ed Miller

- 1977 paper modeled how high vol implies a lower return

- 2001, Miller mentions this strategy in the Journal of Portfolio Management. "An implication of [my winner's curse] theory] is that investors can improve their return relative to risk by exploiting the flatness of the security market line."

- My experience

- First Paragraph of my 1994 dissertation: "This paper documents two new facts. "First, over the past 30 years variance has been negatively correlated with expected return for NYSE and AMEX stocks and this relationship is not accounted for by several well-known prespecified factors (e.g., the price-to-book ratio or size). More volatile stocks have lower returns, other things equal. In fact, one of the prespecified factors, size, obscures this inverse relationship. Second, I document that open-end mutual funds have strong preferences for stocks that are liquid, well-known, and most interestingly, highly volatile stocks."

- All the right people thought it was wrong, 'like saying the world was flat' (true quote from one reviewer). Portion of dissertation made Journal of Finance, so it wasn't that I just couldn't write.

- Created C-corp fund in 1996, tried to get a backer, no success until I eventually started plying it within hedge funds circa 2003.

- Why Important

- Clearly the utility function used by economists is simply wrong

- Big implications for how we model human behavior

- Science as a collective has biases just like individuals

- Smart, educated experts see things that arenât there for decades

- Concentrated selectively on rigor

- Econometric issues (eg, Shanken, 1985, Gibbons 1982), not omitted variables

- My Solution to Why the Low Vol

- Everything is a vice at extremes: an excess or deficit. Risk too can be too little or too much

- Risk is not merely a preference as taught by modern finance.

- Optimal risk is varies objectively across individuals based on intelligence, connections

- Low Vol Anomaly needs relative and standard preferences

- Highlights we are always thinking about ourselves egotistically and socially

- Our desires are both absolute, and relative

- These objectives can conflict when fads arise